Following on from Part I, here I'll unpack how I archive in practice using DEVONthink (DT) as a driver. As I noted in part I, DT is a Mac-only application, and so in order to replicate my setup, you unfortunately need to have an Apple device. I'm actively looking for linux software that can simulate or replicate DT's functionality, as my primary workstation is Artix on a modified LARBS, but I currently know of nothing that compares. In fact, it is pretty much solely DT's capabilities as archiving software that ties me to still using a Mac for some kinds of work.

Alongside documents in DT, I also keep a personal database of notes in plain markdown, which I view and edit in a range of ways (Obsidian, vim or emacs in desktop environments, and iWriter on iPad). I call this database my "PKB", which is a shorthand for "personal knowledge base" I picked up somewhere online. My PKB loosely follows Nick Milo's LYT method for note-taking, and contains notes that range from handy bash commands, to lecture notes, to article drafts.

My Obsidian graph. Edges between notes represent lateral links.

I'll unpack my PKB in more detail in a future post. I mention it here because it structures the way that I use DT. DT is where I read and seed ideas; my PKB is where I grow them as research. In other words, my DT archive exists largely to service the development of my PKB.

An associative archive in DT (or another application) can supplement any research output process, whether it takes the form of a PKB like mine, whether it's a Roam Research database, folders in Evernote, or whether it's just a good old blank Word document.

My DT setup involves several customisations. Some of these are straightforward, and I'll do my best to detail those here in such a way that they can be easily reproduced on any DT installation. Others involve custom Python scripts and external services like Dropbox. If you're interested in the detail of these, or have any questions or comments in general, please do feel free to email me. If you've taken the time to read this, I'd love to hear from you! :)

DEVONthink in a nutshell

DT is ultimately a file manager, comparable to Finder in Mac, File Manager in Windows, or Nautilus or PCManFM in Linux. To get started, you create a database, in which you can then store files of various kinds. With DT, you can then effectively browse and modify the contents of your databases.

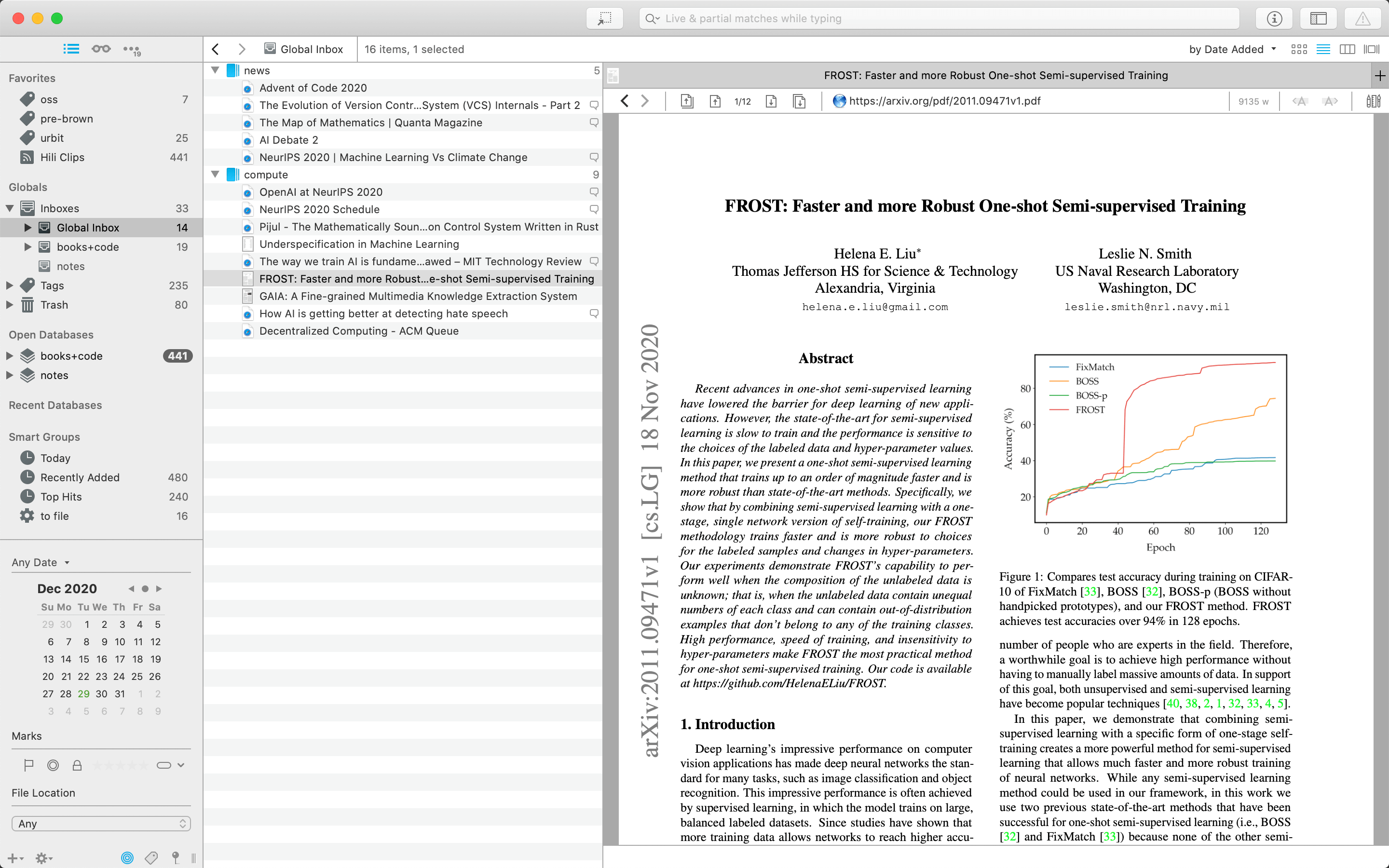

DT is superior to a traditional file manager in a range of ways. Firstly, it is conceived as a way both to find files, and to view them. The left side of the screenshot above looks much like Finder; the right side looks like Preview, or some other PDF viewer. DT's PDF viewing and editing is slim and straightforward, and much more effective than Finder's 'preview' functionality for basic viewing. I've found it capable of everything I want to do regularly with PDFs, including highlighting, adding notes, and jumping to page numbers. If there's ever anything lacking, you can double-click and open the document in another application, just as you would in Finder.

DT doesn't only support viewing and editing PDFs; it provides similar capabilities for most file types that you can imagine: images, CSVs, markdown, and many more. Crucially for my archiving, it supports both .webloc files (which are basically bookmarks for webpages) and webarchives (offline webpages). This support means that I can view webpages alongside PDFs in the same view, treating them as analagous, rather than having to employ a different storage system (such as browser bookmarks) and set of viewing applications for each distinct file type.

DT also offers fluid conversion between document formats. I can right-click to save a .webloc as a webarchive, or to convert a webpage to a PDF. (Webarchives in particular are a revelatory format: because it's HTML saved locally, you can edit it and add in your own highlights, hyperlinks that point locally to other DT documents, and styles as you might with a PDF document.) DT offers a huge range of useful operations: making a new PDF by excising a range of pages from a larger PDF, wordcounts over documents of various kinds, and many others.

Like Finder, you can toggle through a range of different views on the list of files on the left-hand side. You can even modify its orientation with respect to the document viewing panel (which can sit on the right as pictured above, below the file list, or be hidden).

Organisational concepts in DT

There are two primary organisational concepts in DT: groups and tags*. Groups are essentially folders: nodes that exist as the parent to a collection of children documents. Tags are more flexible, and less hierarchical. They are distinct tokens that can be associated with any document, and subsequently used as composable filters to view associated documents.

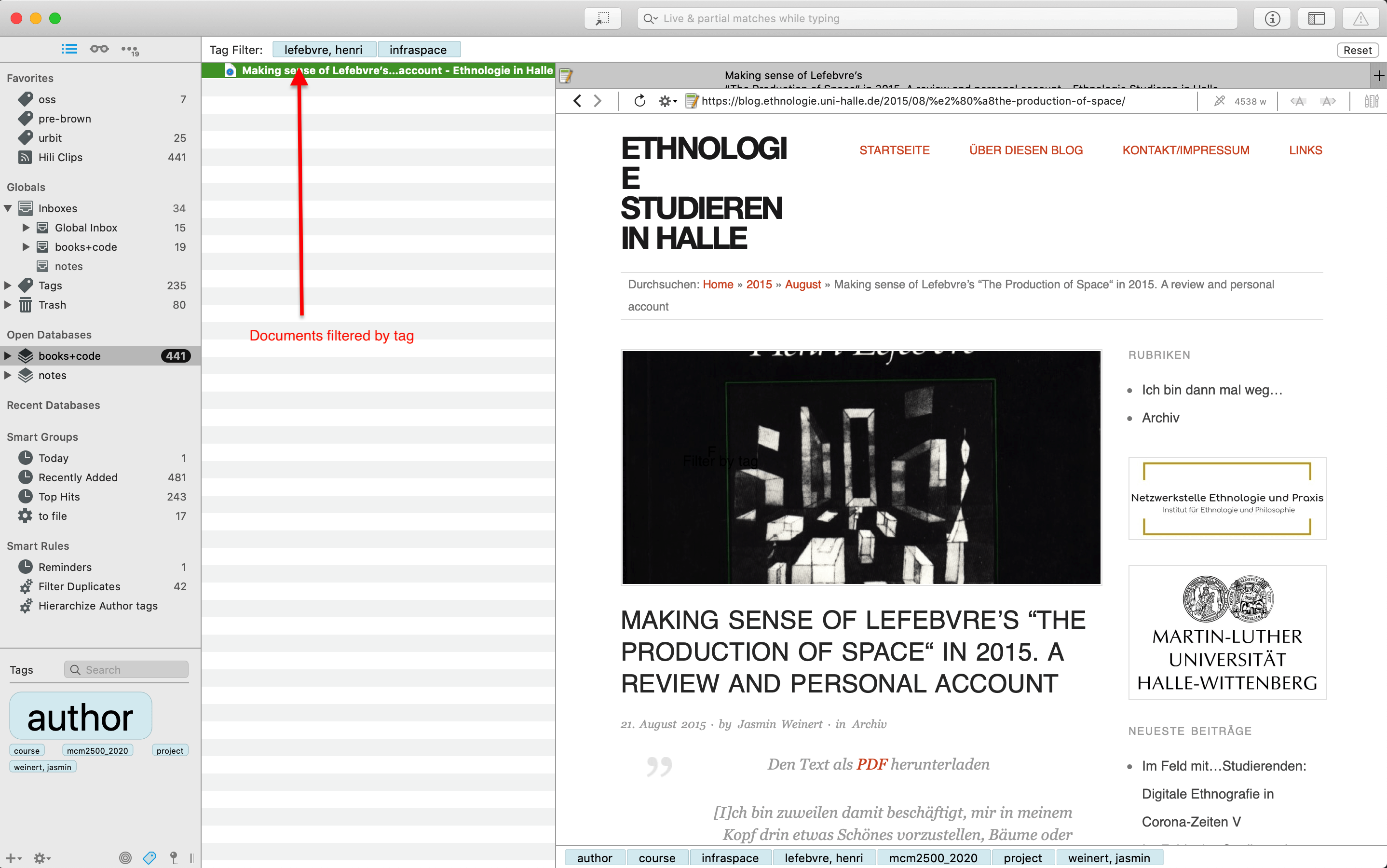

If you've read part I, you won't be surprised to hear that I almost never use groups, and use tags extensively. DT's tagging system is what makes it so effective as an engine for associative archiving. You can filter for documents associated with one or more tags in any database:

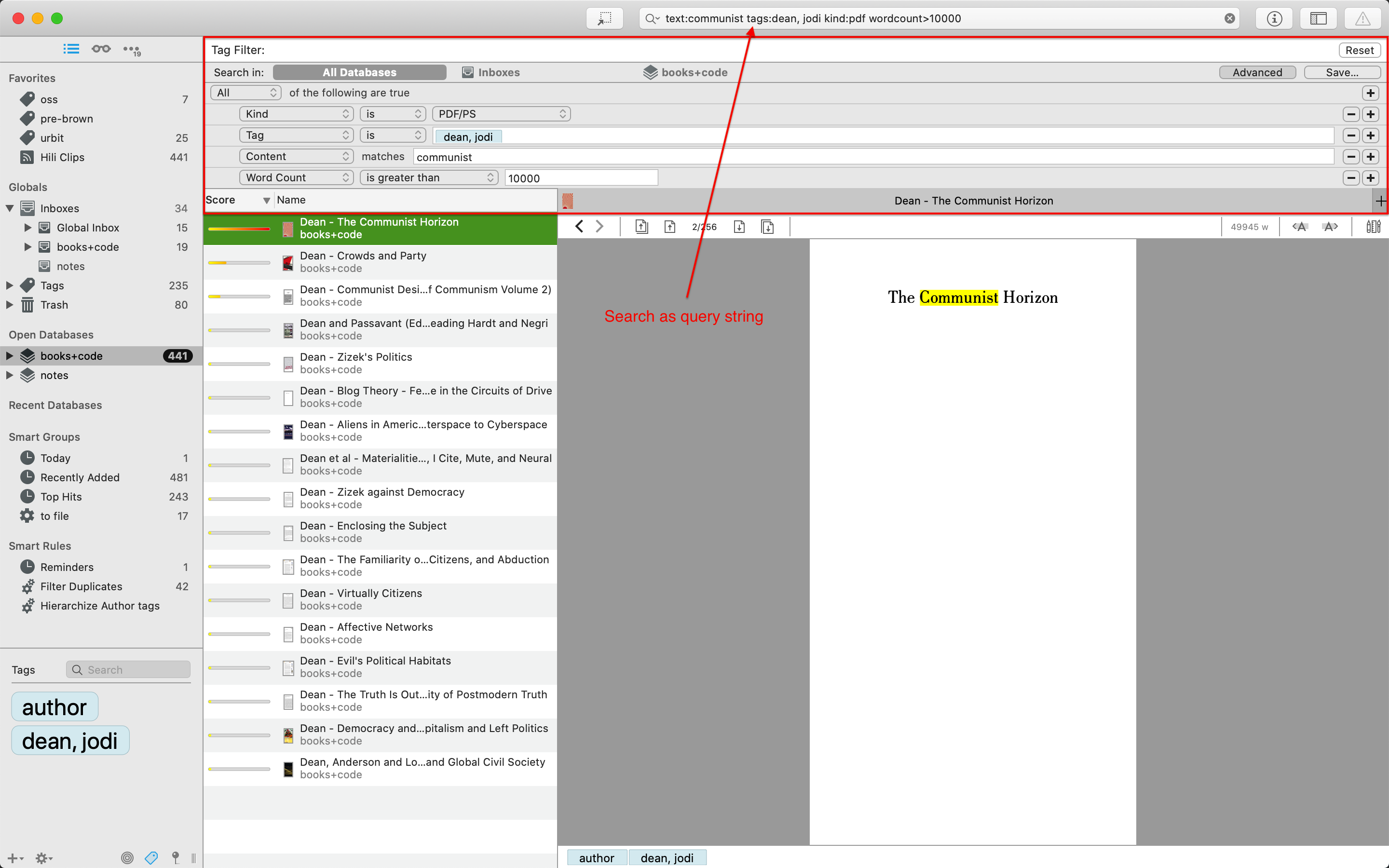

In addition to basic filters, i.e. for documents that are associated with a particular tag, you can compose arbitrarily sophisticated filters over a database to retrieve matching documents. These filters can make use of document tags; but also all of their other metadata, such as date created, date modified, document kind, to name just a few:

In addition to this metadata query language, DT provides impressively effective full text search. This operates over documents of all kinds: PDFs and webarchives alike, any document that has text that DT's indexing engine can pick up on. (Certain versions of DT also provide support for OCR-ing PDFs that don't explicitly contain textual data.) Combining this with tags, I can query for documents in DT using arbitrarily complex directives, such as "Give me all PDF documents authored by Jodi Dean that contain the word 'manifesto' that have more than 10000 words". Results are ranked using a scoring algorithm, so that must relevant results come to this top. Searches can be done either succinctly via DT's query language in the search bar, or visually using the provided GUI.

Associative archiving in DEVONthink

The three primitives of associative archiving as I outlined them in part I are: projects, associative tagging and an inbox. Here's how I implement each of these using DT.

Projects

For each new project in DT, I simply add a new tag, and start attributing it to documents that exist in that project. Seeing all the documents in a project is then as easy as filtering for a tag.

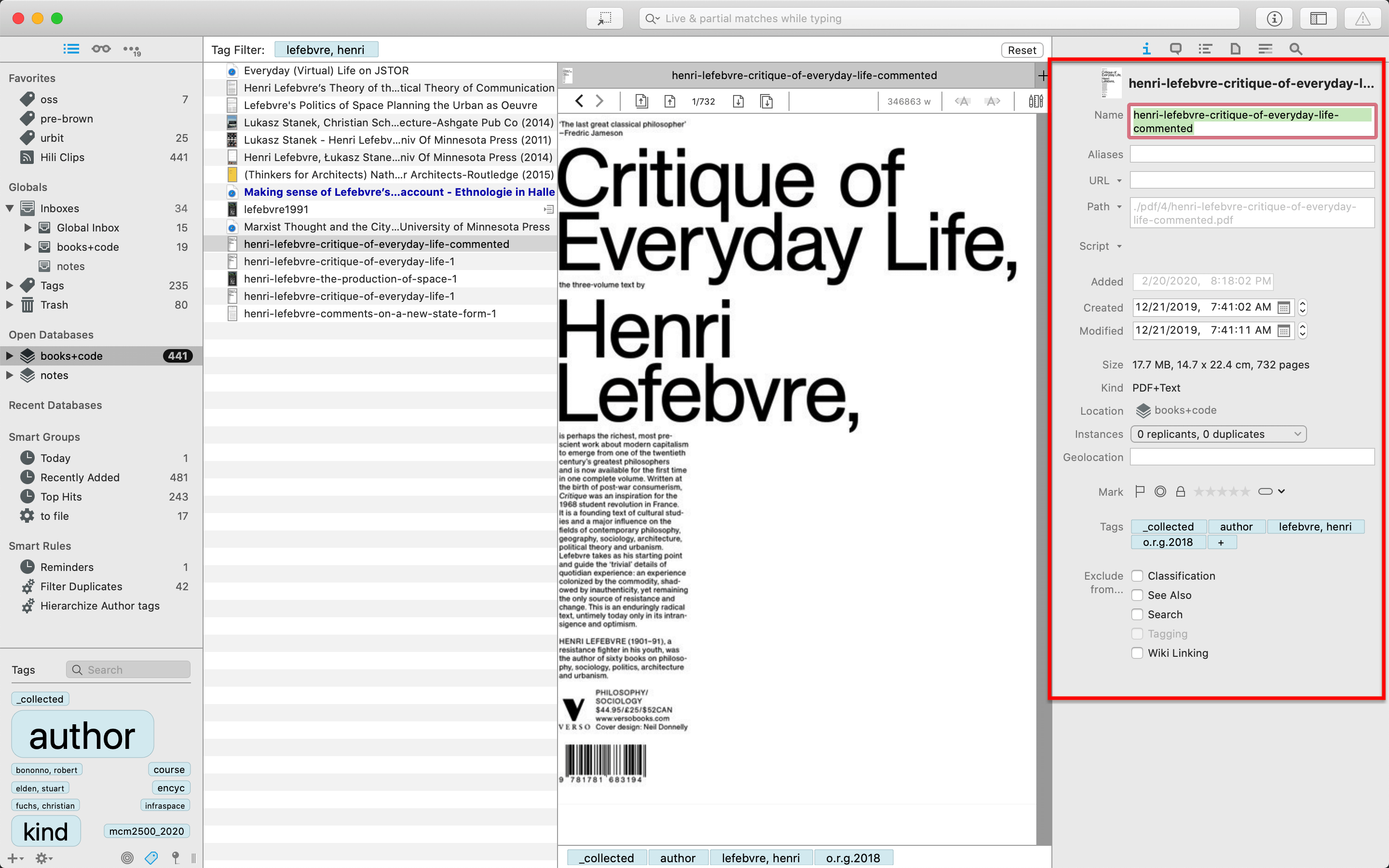

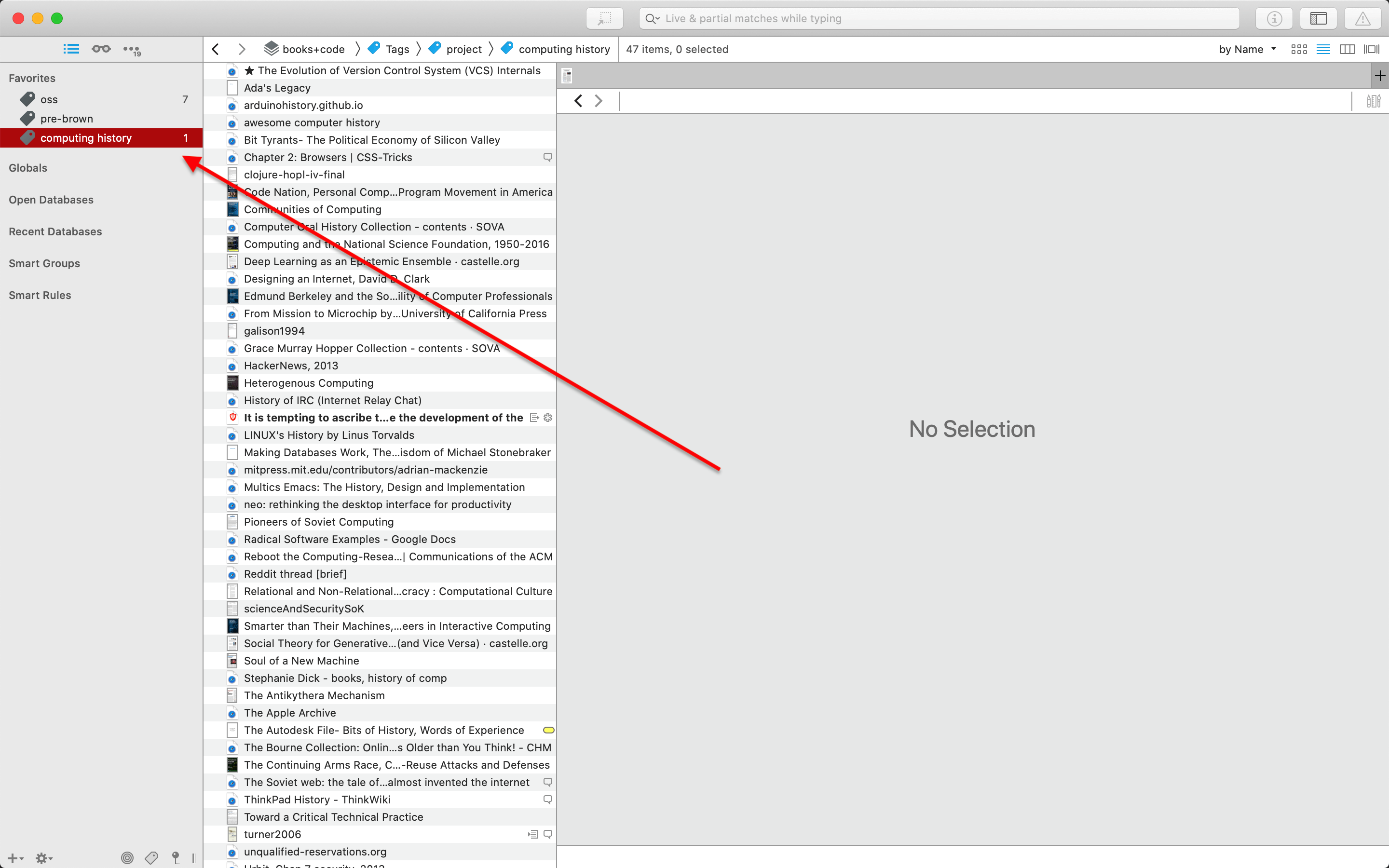

In addition to working as a filter, tags exist as distinct entities in DT. This means that they can be searched for, added in groups, and so on. One shelf that DT offers in its global sidebar (on the leftmost of the screen below) is a list of 'Favorites', to which you can add any kind of entity. By adding a project tag such as 'computing history' to my Favorites, I create a distinct workspace for that project, which will dynamically show me all documents within that project. From this workspace, I can then further search and filter over tags, metadata, or contents.

Associative tagging

I have a few special categories of tags in order to keep my archive clear and usable. The architecture of my archive's tags is an eternal project: I'm endlessly creating, renaming and consolidating tags together in order to make them more effective as filters and search concepts for my research. This dynamic change is possible in DT, because tags are more flexible than folders: deleting or renaming one won't remove associated documents or break other connections, it will just remove that tag.

Project tags* - correspond to a project as described in the section above.

Author tags* - a tag for the author of a document. This is a bit more robust than relying on DT inferring the appropriate metadata, I've found, as PDFs and webpages sometimes don't contain the information appropriately for DT to pick up. Author tags exist in my archive in the format "lastname, firstname", e.g. "dean, jodi". Any tag that includes a comma I treat as an author tag.

Kind tags* - a tag that marks some quality of a document that I want to track(i.e. it's 'kind'). This ranges from my own interpretations of the document ('interesting', 'difficult'), to its genre ('literature', 'journalism'), to its medium ('podcast', 'video'), to some parenthetical note or impending course of action ('toread', 'reading', 'unread').

Journal tags* - the journal or publication source of documents ('duke university press', 'jacobin', 'verso'). As in the case of author tags, this is more resilient than relying on metadata inference.

Field tags* - disciplinary or otherwise structuring fields in which documents exist. I mainly use these as ways of capturing pockets of technical literature in computer science, i.e. 'databases', 'decentralised', 'p2p'.

Course tags* - tags for seminars that I take or teach. All of the readings are tagged with the course tag ('MCM 2500 2020'). I used to use tags for particular weeks of content as well, but this gets complicated if certain documents are read in multiple courses (as they may be read in week 1 of one course, and week 4 of another). Instead I now rely on the course's syllabus (which can be found using the type tag 'syllabus') to preserve the course's progression.

The basic guiding principle here is that my tag architecture should reflect the way that I conceptually order documents, so that retrieval from the archive is as simple as composing a few tag/concepts together. Search is not the only application though; wandering through my tag architecture can also lead to serendipitous discovery of links between different kinds of content. Keeping the archive 'flat' by default encourages this latter kind of discovery, and keeps categorisation from ossifying and stymieing creativity rather than supporting and structuring it.

The inbox

The final component of the associative archive is an inbox for incoming documents, which are either to be read or simply shelved for later. DT comes natively with the idea of a 'Global Inbox' that represents a holding shelf for documents before they go into whichever database.

It is easy to drag-and-drop files such as PDFs if they're local into the inbox, and DT also provides extensions for Safari, Chrome and Firefox to easily 'clip' webpages into the inbox.

I use DT's inbox as my primary way of keeping track of links and documents to read. Because it exists separately from the rest of my database, I can sync it with the mobile version of DT, DEVONthink To Go, without having to worry about taking up all the space on my tablet with all my PDF documents (which can be stored on the Cloud and synced on demand if you prefer). My DT inbox becomes a 'Read Later' space for everything incoming from either the web or that folks have sent me as PDF.

If I didn't have an e-reader, I would probably read PDFs on my ipad via DT To Go as well: but because I start at a glowing blue screen so much in any case, I make a point of reading everything I can on my e-ink Remarkable tablet. PDFs basically sit in my DT inbox for as long as I'm reading them, as a kind of reminder that I need to, and then once I have finished with them on Remarkable, I export them and replace the placeholder documents in DT with the annotated versions.

To be continued…

I only intended to have two parts, but in Part III I'll explain how I manage annotations on documents in DT. As I'll explain in more depth there, this is slightly beyond the scope of DT as an 'archive' per se, as it gets into how I use my DT archive to write and produce my own research.

There might also be a part IV, in which I'll go into more detail about my PKB and writing process. Both my annotation system and my PKB are more freshly minted than my DT archive, and as such they're still developing and are subject to change and improvement. They work pretty well for me at the moment, though, so I'll write up their processes in the hope they're useful/interesting to some.